Bienvenue!

Internationalization and localization efforts have a lot in common with web accessibility. Both are domains of usability with the express goal of ensuring audiences are included by an interface, rather than excluded from it. Both benefit heavily from forethought and careful strategy, rather than attempts to retrofit improvements after the fact. Both are often worked on by people who are building outside of their own lived experiences.

At the intersection of internationalization/

I’ve personally found it really difficult to find practical, useful guidance for multilingual web accessibility specifically — so let’s change that! Here are a few tips for multilingual web accessibility that I’ve picked up so far, largely from my experience as a developer. For these tips, I’m generally assuming you have a fair amount of control over, or input into, your site’s design, markup, styles, and scripts. Content management systems and site builders are their own cans of worms that I don’t have a lot of experience with, so I’ve opted not to cover them in this post. I’m also sure this won’t be a complete list, so please reach out on Mastodon if you think of something I’ve missed!

Declare the Content Language

The lang attribute is used to specify the human language of a given element. It takes an ISO-defined code for the primary language, which can then be followed by additional subtags for specifying region and other possible variations — though to maximize compatibility with clients and assistive technologies, W3C recommends keeping your language tags as broad as possible, only using regional subtags or other variant subtags when they’re absolutely necessary to understand the content.

Declaring content’s language is especially useful for screenreaders and text-to-speech software, which use the lang attribute as a cue to load the right pronunciation rules. lang can improve the braille display experience, too; the JAWS screenreader uses language detection to load users’ language-specific braille profiles, for instance.

There are two main times we need to set the lang attribute: once when establishing the page’s primary language, and then again whenever elements or bits of text are set in some language other than the page’s primary language.

Setting the Page’s Primary Language

To set a page’s primary language, specify the lang attribute on your <html> element. For instance, this blog has <html lang="en"> to mark it as English. Specifying the correct language this way is incredibly low-hanging fruit and yet, it consistently shows up as a prevalent issue in WebAIM’s yearly report of the million most popular homepages’ accessibility.

One thing to watch out for: some site generators or boilerplate projects will prefill the page language with "en" by default, so if you’re using one of these tools to build your own site in some language other than English, be sure to update that, as leaving an inaccurate lang can have unfortunate consequences. Automatic accessibility scanners are just looking for the existence of a page-level lang attribute, so they’re not likely to flag inaccurate lang values for you.

For those playing WCAG Bingo at home, specifying the page’s primary language with <html lang> is pretty much the technique for meeting Success Criterion 3.1.1: Language of Page, which is a Level A requirement.

Phrases in Secondary Languages

If the page contains a word, phrase, section, whatever in some language other than its primary language, then that secondary-language content should be wrapped in an element that has its own lang attribute. The cheerful Bienvenue!

heading earlier has lang="fr" to mark it as French, for instance.

<h2 lang="fr">

Bienvenue!

</h2>Screenreaders and text-to-speech software that support the appropriate languages should switch between languages fairly seamlessly, adopting the right pronunciations at the right time.

Additionally, supplying the lang attribute is useful even when the screenreader or text-to-speech doesn’t support that language. For instance, if it doesn’t have a particular language installed, JAWS will announce the language name before garbling secondary-language text. This gives JAWS users a kind of troubleshooting step to remedy the situation; if they had wanted to read that secondary-language text as it was, they would need to install the appropriate language. If they opt not to (say, not downloading a language they don’t already understand), then at very least, they have context as to why their screenreader couldn’t announce certain content.

Don’t go overboard with this markup power, however. Well-understood loanwords, for instance, have become part of the primary language, and thus don’t need to be specially marked up. You wouldn’t need to mark up the word rendezvous as French, for example, because the word has already become pretty integrated into English.

Marking up phrases and elements in secondary languages with their own lang attributes is pretty much the way to meet Success Criterion 3.1.2: Language of Parts, which is a WCAG Level AA requirement.

Support Alternate Writing Directions

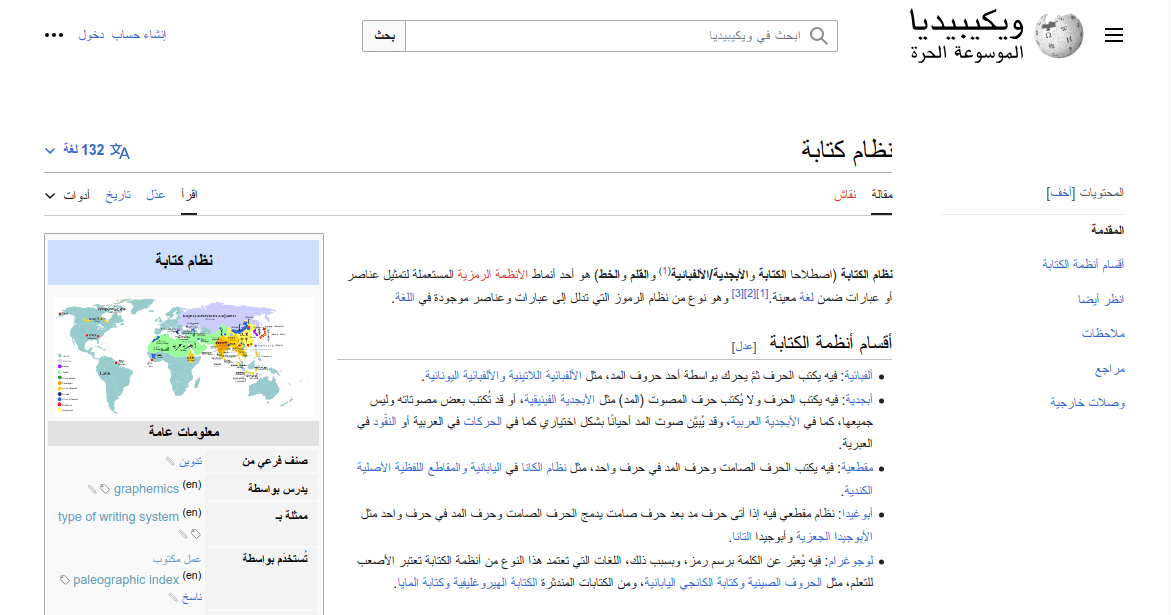

A language’s writing direction has knock-on effects for the page layout as a whole. If you compare left-to-right site layouts with right-to-left site layouts, for instance, they’ll typically be horizontally mirrored inverses of each other. The stuff that was on the top left in one layout will usually be in the top right, and vice versa, when the writing direction is flipped.

This is especially noticeable in alternate language versions of the same site. Take Wikipedia, for example. Where English Wikipedia aligns navigational elements like the site logo and the table of contents to the left side of the page, Arabic aligns those elements to the right. Similarly, the supplemental infobox found on the right side of the English article is instead found on the left side of the Arabic article.

Following the layout conventions of a given language or locale will make your site’s visual hierarchy more familiar and predictable, even if someone’s never seen it before. Beyond being culturally cognizant, having a predictable visual hierarchy brings with it accessibility benefits. For one thing, familiar visual hierarchies reduce cognitive load for users with cognitive disabilities. For another, predictable placement of information and controls can benefit screen magnification users who can’t necessarily see the full layout at once by making it less tedious to find what they’re looking for. These benefits mean the inverse is also true, though: while unfamiliar layouts will be frustrating for anyone, they’ll be especially alienating and difficult for disabled users.

Fortunately, web technologies have gotten way more flexible at handling text direction thanks to CSS's logical properties and values. Logical properties and values let us define margins, padding, borders, text alignment, flex layouts, and more in ways that will automatically adapt to a language’s writing direction. For example, the margin-inline-start property is akin to margin-left in left-to-right languages, margin-right in right-to-left languages like Arabic and Hebrew,

and margin-top or margin-bottom in vertical writing modes such as those sometimes used for Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Mongolian text… all with one tidy CSS rule. Nifty!

Logical CSS isn’t a cure-all for every writing direction-based layout issue, however. There are still some spots where we’ll need an intentional content strategy. One scenario I’ve encountered is hero banners. For instance, if our hero banners involve overlaying some text on top of a splash image, take care that right-aligning the hero’s text doesn’t suddenly place it on top of the busy detail of the splash image, posing color contrast and general illegibility issues. Plan for right-to-left layouts from the get-go, whether by supplying right-to-left specific hero images; ensuring hero images are safe to mirror (i.e. lacking any text, symbols, or logos that would look amiss upon mirroring); or by redesigning the heroes to avoid overlaying altogether.

Handle Text Expansion with Adaptive Layouts

Responsive, fluid web design is critical to account for the wide spectrum of devices people may be using. From an accessibility perspective, following robust responsive web design techniques ensures that if, for instance, low-vision users need to zoom in or bump up the base font size in their browsers or operating systems to be able to read a webpage, they can do so without the page falling apart.

However, when multiple languages are involved, responsive techniques become even more critical because of the potential for text size expansion. Words and phrases that are short and tidy in the source language might balloon dramatically when the target language…

- …uses longer words in general

- …has wider characters

- …assembles long compound words that provide fewer natural line breaks (looking at you, German)

- …requires that abbreviations be written out in full instead

In one instructive example from the W3C Internationalization Activity, when translating their site into Italian, Flickr translated views, as in the number of times a given image had been seen, as visualizzazioni, going from just five characters in English to 15 in Italian, a 300% increase. And as the W3C Internationalization Activity goes on to note, this is par for the course: English text often doubles or triples in length when translated into Italian and other European languages.

Cramming this kind of text expansion into pixel-perfect layouts designed with anglocentric assumptions in mind is a recipe for disaster. In the Flickr example, we can imagine how, if a view counter had been tucked in the corner of some limited-width container like a card, the string “visualizzazioni” could cause some overflow issues, particularly if the design also tried to cram in other elements inline, too. Navbar items, too, will need to pack longer words and phrases into tight spaces. And bringing this back to accessibility, all of this is especially true if the user also needs to zoom in or bump up their browser’s base font size. Text expansion and the need to zoom/resize all but guarantee users will reach any dreaded overflow issues your layout might have sooner.

One common tactic for attempting to rein in overflow is text truncation. However, truncation poses its own accessibility issues and, to quote Karen McGrane, it’s infamously not a content strategy (⚠️ results may be NSFW). It’s usability’s way of throwing in the towel. We can do better, especially where navigation and pages’ critical functions are concerned.

Instead, tackle these issues at the root:

- Follow responsive web design best practices instead of striving for pixel-perfect layouts

- Avoid capping elements’ dimensions to maximum widths or heights

- Give your UI elements plenty of room to grow should they need to accommodate longer text

- Build layouts that anticipate text wrapping onto new lines

- Ensure design comps reflect the messy asymmetry of the real world from the get-go, rather than only demonstrating cases where content follows symmetrical, neat, tidy, elegant happy paths

Account for Text Shrinking with Defensive CSS

Where text expansion in translation can cause problems by exacerbating possible overflow, text shrinking in translation causes problems by making elements too small to use. This is especially troublesome for links and buttons that lean on their text contents’ intrinsic lengths for their own sizing.

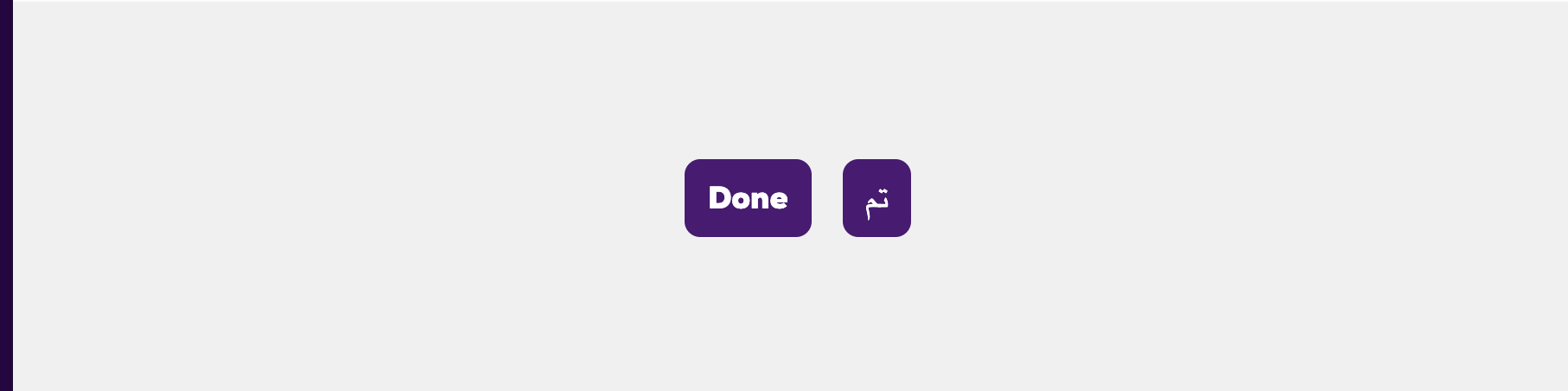

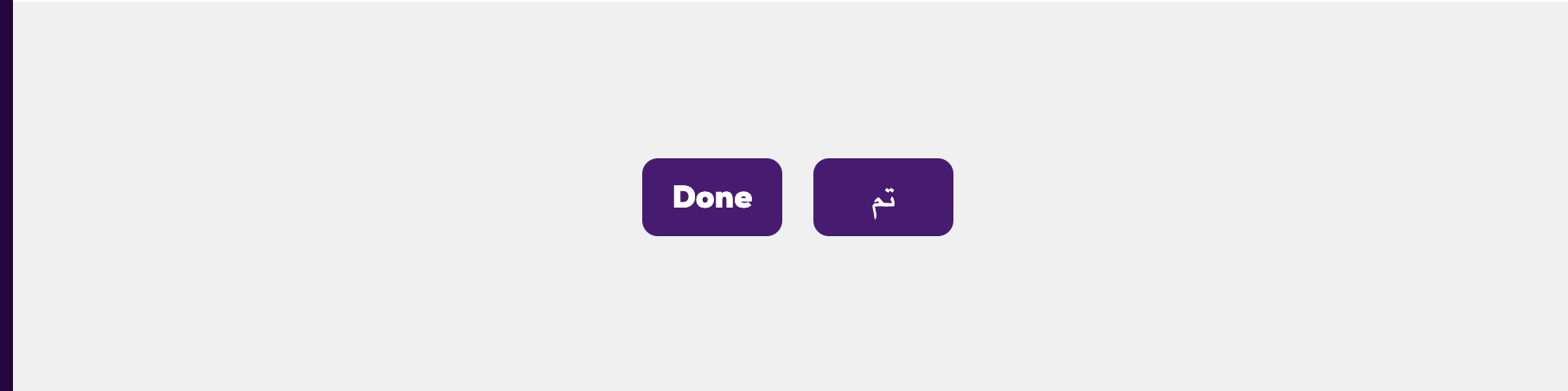

To borrow an example from Ahmad Shadeed, imagine we have a confirmation button that says Done

in the English version of the site. This same button might read تم

in the Arabic version. Yet, the difference in widths between these two buttons is stark:

Even with a little bit of added padding and typographic adjustments, the Arabic version of the button would be pretty fiddly, especially on touch devices. This can make the site harder to use for anyone with motor/mobility disabilities such as Parkinson’s that make hitting precise targets difficult. This is especially problematic in cases of primary action buttons (like submit buttons and confirmation buttons), navigation links, and call-to-action links.

Fortunately, we can use the defensive CSS technique of applying a minimum width. We could set it to something like 44px, to hit the minimum target size recommended by WCAG's Level AAA Success Criterion 2.5.5: Target Size (Enhanced), or we can go even wider if we want to give the control the proper oomph and gravitas of a primary action button or a call to action.

.button {

min-width: 90px;

}

You can also similarly set a minimum height, especially if you plan to stack interactive controls. Just be sure to only set the minimum height and width this way; don’t cap controls like this to fixed dimensions.

Use Readable Typography

The specifics of what legible typography entails for your design will depend heavily on which languages you support. Where possible, lean on the typographic conventions established for a given language or script. Here are some things to look for:

- Typefaces: Pick a typeface that has been intentionally designed for the particular language. When in doubt, consider leaning on system fonts: familiarity contributes heavily to legibility, and the performance boost won’t go amiss either.

- Font variations: Not all writing systems support capitalization, boldface, italics, or underlining like the Latin alphabet does. Inserting these western typographic conventions into writing systems that don’t traditionally support them can clutter the text, making it muddier and less legible.

- Font size: Writing systems with more intricate/complex characters often benefit from a larger font size.

- Tracking: Fixed-width/monospace writing systems like Chinese, Japanese, and Korean (CJK) characters can benefit from wider tracking (the spacing between characters), though you should first check whether your font has handled that tracking baked in already.

- Line height: Average character height, diacritics, ruby text, and more can all contribute to a line of text feeling crowded. Writing systems with these features usually benefit from larger line heights.

- Line length: Fixed-width/monospace writing systems may need fewer characters per line to stay readable.

For some concrete examples of some of these typographic differences and their requisite adjustments, I highly recommend reading through An Introduction to Writing Systems & Unicode: Typographic Differences

by r12a.

Make Sure Every User-Facing String Gets Translated

Accessibility work often leans on strings of text that aren’t necessarily ever made visible. These include…

- Attributes that expose arbitrary text values, such as

alt,aria-label, ortitle - Visually-hidden (née “screenreader-only”) help text

- Live region announcements

<title>and<desc>nodes within SVGs

Unseen as they are, these strings are more prone to getting missed in translation workflows. This means that swaths of the interface will still be rendered in a fallback language that’s unfamiliar to the reader. An aria-label="Close" on a dialog’s close button, for instance, won’t really do someone any good if they don’t speak English. Text meant to improve access instead introduces more barriers. (And if you’re relying on automatic translation as your internationalization strategy, be forewarned that there are many cases where attributes like aria-label won’t auto-translate)

To ensure a multilingual site is accessible across languages, it’s critical that hidden strings are included in whichever translation workflow your site uses, even if they’re hidden or buried inside attributes. Make a practice of never using a hardcoded string for user-facing content.

One gotcha I’ve especially noticed here is with dynamically generated text. While an English-only site might be content to build up strings using concatenation or template literals…

editButton.setAttribute('aria-label', 'Edit ' + title);

// or:

editButton.setAttribute('aria-label', `Edit ${title}`);…these approaches don’t really carry over well to any sort of multilingual context, even if you translate the strings’ individual components…

editButton.setAttribute('aria-label', translate('edit') + ' ' + title);

// or:

editButton.setAttribute('aria-label', `${translate('edit')} ${title}`);…because different languages have different word orders. German users, for instance, wouldn’t expect “Bearbeiten [title],” but rather, “[title] bearbeiten.” Instead, make sure that your translation methodology supports placeholders for interpolation, rather than trying to build up the individual bits and bobs of a longer string within the interface. This is just as much of a need for visible labels as it is for hidden text, but in my experience, this is easier to forget (and much harder to catch when it does happen!) for hidden strings.

Make sure every user-facing string gets translated

is, for sure, far easier said than done. To that end, there are a few things you could do to reduce your reliance on hidden text that might get missed in localization:

- Where possible, use visible text labels, minimizing the use of hidden text. This will better surface any translation gaps and reduce the chances of discrepancies between the visible and aural user experiences.

- Lean on semantic elements and attributes, including ARIA attributes, to convey UI elements’ roles and states so that assistive technologies can fill in the user’s preferred localizations/translations.

Ensure Consistent Microcopy

Microcopy is all the little bits of text that appear throughout the site: the nav links, the sidebar headings, the form field labels, stuff like that. When microcopy is written and used consistently, the site layout becomes much more predictable, and users won’t have to guess as much about how the site functionality works, which in turn:

- Reduces the cognitive load of using the site, which especially benefits cognitively disabled users

- Increases confidence in a control’s functionality, even when someone can’t see any or all of the surrounding context

- Helps voice control users build up a mental model of the commands they can use to target their desired elements, without which, they’d need to resort to tedious workarounds

And speaking of voice control, there’s one especially pernicious kind of accessibility bug that can crop up as a result of inconsistent microcopy. Consider a site where a translator opts to translate Delete

as Löschen

in German. Later, a translator translates the string Delete file

as Datei entfernen,

opting to use a different verb this time. Generally, professional translators will avoid discrepancies like this, but given a large enough project with enough translators and over a long enough time, inconsistencies can happen.

While both of these may well be viable translations of these strings, a problem arises when, as a result, we localize this button:

<button aria-label="Delete file">

Delete

</button>as…

<button aria-label="Datei entfernen">

Löschen

</button>(Thanks to Moritz Rebbert for suggesting this particular example!)

Suddenly, the German version of our site has a Success Criterion 2.5.3: Label in Name (Level A) violation that the English version doesn’t. This can confuse sighted screenreader users, as well as make it much harder for voice control users to target this button in their commands. However, neither string alone is the issue. Rather, this issue emerges from trying to use these two strings together. What’s more, this isn’t the kind of issue that can be caught by spot-checking the source language version of the site, and it is exactly the kind of issue that can emerge as a web project grows in complexity.

From the translator side, inconsistent microcopy can be mitigated by adhering to detailed styleguides, regularly checking translation consistency tooling, and periodically reviewing older translations.

Designers and developers can prevent these kinds of Label in Name collisions in the first place by reworking the underlying design and implementation to not be so dependent on aria-label or other hidden text, and instead surfacing context through visible text. While I don’t think we can avoid aria-label entirely, we can pare down the chances something like this can come up.

Vet Third-Party Libraries for Multilingual Accessibility

You can invest a lot of effort into the above few tips, and it can all be dramatically undercut by introducing third-party code that hasn’t been so thorough.

If you use component libraries or other third-party scripts on your site or web application, it’s important to vet those third-party libraries for accessibility. However, if those third-party libraries aren’t also properly considering internationalization and localization, this can throw another wrench in the works. After all, just like your own code, a component library’s aria-label attributes or live region announcements are limitedly helpful to users if they’re all hardcoded in one language. Similarly, a beautiful UI component will stick out like a sore thumb if it doesn’t readily adapt to other writing directions. What’s more, fixing these gaps via issues or code contributions will generally be trickier and slower than it would have been to fix your own code.

Unless a third-party library happens to support all the same languages and locales that you do, with translations that you’re happy with, look for libraries that:

- Support you passing in your own (localized) strings for attributes, announcements, etc.

- Either provide their own styles for writing direction support or are easy enough for you to style yourself

Adieu

Multilingual web accessibility is, in many ways, a stress test for both your accessibility standing and your internationalization/

I’m constantly in the process of learning new things, especially about accessibility and internationalization, and I’m sure this article is nonexhaustive. If there’s something I’ve missed, let me know on Mastodon!

Further Resources

- All articles from the W3C Internationalization Activity

- Translations of current W3C standards and drafts

On Language Learning for Screen Reader Users,

by Florian BeijersWhat they don’t tell you when you translate your app,

by Eric BaileyCSS for internationalisation,

by Chen Hui JingThe Most Comprehensive Guide to Web Typography in Japanese,

by Masaharu Hayataki

Originally posted on my blog, benmyers.dev, as Lost in Translation: Tips for Multilingual Web Accessibility

]]>