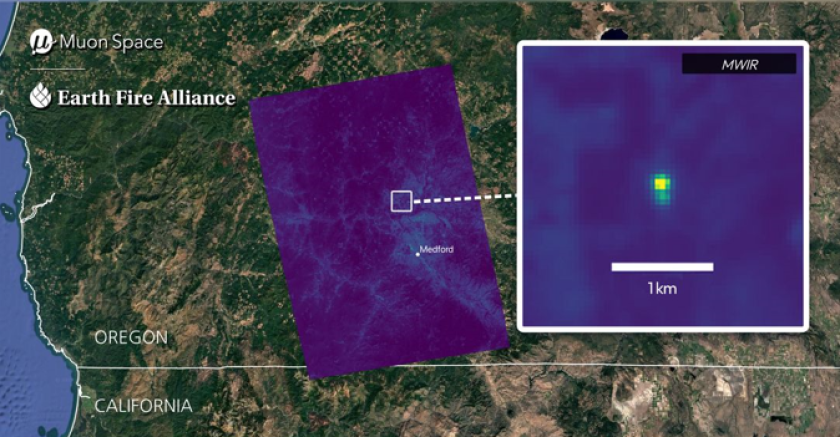

Two fire agencies in the U.S. are now getting access to FireSat, a satellite system that researchers say could fundamentally change how the world detects and understands wildfire. The system captures detailed images of emerging fires from low Earth orbit using sensors precise enough to spot a blaze the size of a school classroom.

Watch a side-by-side resolution demo show how FireSat compares to traditional satellite tools in the video below.

According to the data from the National Fire Incident Reporting System, fire departments already respond to far more false or unnecessary calls than real fires. Further overreporting could waste fuel, desensitize responders and risk loss of trust in the technology.

In 2023, fewer than 4 percent of calls involved confirmed fires. That’s compared to 8 percent that were false alarms, classified as alarms triggered by system malfunctions, dust or cooking smoke. Another 12 percent were “good intent” calls which were dispatches based on well-meaning reports that turned out to be steam, controlled burns or vanished smoke.

WHAT IS FIRESAT AND WHAT MAKES IT DIFFERENT?

Muon Space and Earth Fire Alliance

FireSat builds on that technology by providing sharper resolution that can detect even small 5-by-5 meter fires. Its multispectral sensors are designed to cut down on false positives, giving first responders a clearer, more trustworthy picture of fire intensity and location, especially in the early stages of ignition.

The first FireSat satellite launched in March, and its first three public images have just been released.

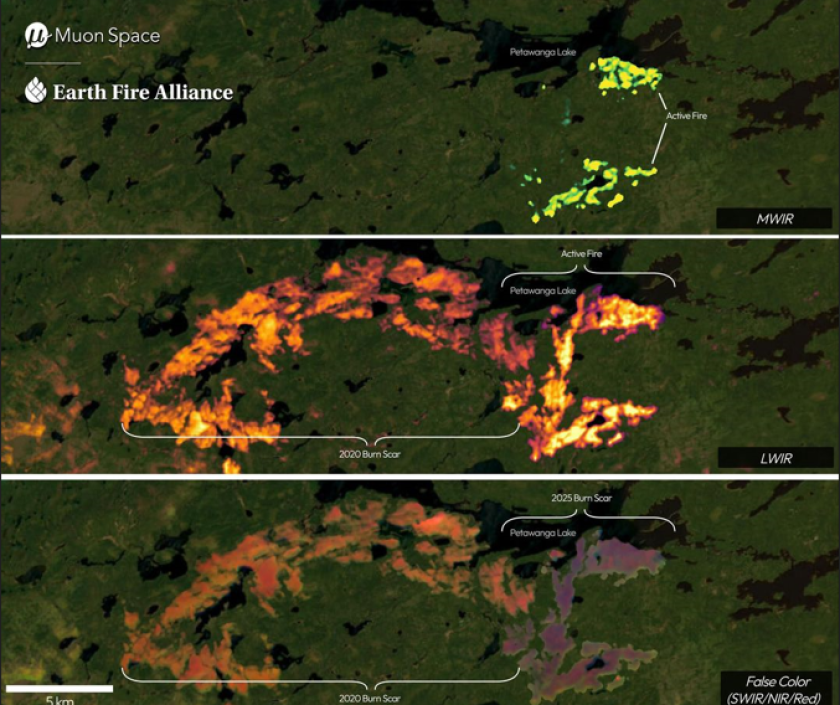

“We’re already seeing more fire on the landscape than we know about,” said Brian Collins, executive director of Earth Fire Alliance and FireSat’s project lead, during a media roundtable this week. Earth Fire Alliance formed in 2024 as a global nonprofit to deliver satellite-based insights that support faster, more-informed decisions about wildland fire.

By early summer 2026, FireSat plans to have three more satellites operational and provide insights to fire agencies, scientists and other global partners. The eventual goal is a constellation of 50 low Earth satellites that will see the whole globe every 15 to 20 minutes, in theory spotting a fire both when it starts, as well as collecting data about a fire’s full evolution.

“We also can pick up low-intensity fires, like grass fires, which no other system can pick up from space and very few even aircraft systems can pick up unless they’re flying at low altitude, at full deployment,” said Collins.

FALSE POSITIVES AND WILD GOOSE CHASES

According to Vice President of Infrared Missions for Muon Space Cathy Olkin, hundreds of first responders were interviewed about what they needed most to best do their job in order to shape the flow of the program.

Kate Dargan Marquis, a FireSat board observer and former California state fire marshal, brings firsthand experience to that process. Dargan Marquis began her career as a firefighter in Santa Cruz in 1977 and spent 30 years with CAL FIRE, including many hours flying over active wildfires. She said that vantage point gave her a deep appreciation for aerial intelligence early on.

Muon Space and Earth Fire Alliance

FireSat relies not only on high-resolution imagery but also artificial intelligence and machine learning to filter the noise. These tools help ensure the satellite captures actionable data, not just images.

Chris Van Arsdale, climate and energy lead at Google Research and chairperson of the Earth Fire Alliance board, said early fire detection is inherently tricky.

“There’s a lot of things that can be mistaken for a fire,” said Van Arsdale. “Like a sun glint or really hot roof, industrial heat. AI is very good at doing this sort of filtering for us.”

HOW WILL GOVERNMENTS AFFORD IT?

The FireSat initiative is led by the Earth Fire Alliance, a global nonprofit supported by Google Research, along with philanthropic organizations including the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the Environmental Defense Fund.

According to Collins, the intent is to keep the project low-cost or free to fire agencies when it becomes operational in the middle of next year.

WHAT COMES NEXT?

If FireSat works as intended, the data it gathers could fundamentally shift how the world anticipates and responds to wildfire.

“It would be great to live in a world where we've removed uncertainty about how wildfires will spread, about where they will be in three hours or 10 hours,” said Van Arsdale. “But we need data to do that. There'll be a new era for earth science and a new era for risk management.”

Van Arsdale said FireSat’s ongoing data collection could create an unprecedented look at how low-intensity fires behave worldwide.

But until then, researchers are planning on several failures that will be opportunities to refine the technology, and create better data. A false positive is a training moment, while a missed fire can become a tragedy.

“The more data we collect, the more we’ll understand about fires,” said Collins. “[We’ll] begin building a new body of knowledge about what low-intensity fire looks like across the planet.”